Triggered by Russia’s push to turn the military tide in Syria in Assad’s favor, Washington D.C. is currently seeing renewed debates about the need to revise the administration’s Syria policy. Prominent voices, such as former White House Coordinator for the Middle East Phil Gordon, have advocated for striving for a negotiated interim solution in Syria that defers the question of Assad’s fate. Bente Scheller, hbs office director in Lebanon, addresses some of the underlying myths and arguments shaping the current debate.

Argument: The objective of equipping and training a vetted force able to degrade and destroy the “Islamic State” (ISIS) has proven unachievable.

Response: The failure of the U.S. train and equip program should come as no surprise. The fear prevalent in the U.S. administration of accidently training Islamic fighters is understandable. But the Pentagon’s recruitment strategy should nevertheless cast some serious doubts given that merely 54 out of 5,000 aspired fighters actually completed their training. How is such a force supposed to “degrade and destroy” potentially ten thousands of ISIS fighters?

There are several reasons why the U.S. train and equip program has so far failed: First, trust in the U.S. has hit rock bottom in Syria: The famous red line that Obama did not adhere to is partly responsible for this lack of trust. Another factor relates to the U.S. strategy in southern Syria, where support for the rebels was always discontinued exactly when they were becoming dangerous for Damascus.

Second, the recruited personnel had to commit to only fight against ISIS rather than Assad. This is not a good premise for those who are being bombed from the air exactly because they fight against ISIS. Most Syrians perceive ISIS and Assad as equally threatening and necessary to fight back against.

Third, mistakes were made with regard to the protection of families: U.S.-trained fighters in particular have to fear brutal acts of revenge should they be captured by ISIS. The same applies to many of the opposition fighters’ families. The U.S. applies a similarly grotesque type of clan liability: Family members of opposition fighters- including those trained by the U.S.- are not allowed to take part in its resettlement program.

In short: the U.S.-trained Syrians continue to be the target of air bombardments by the regime while not receiving air cover if attacked; there is no protection or resettlement program for them or their families; they are not allowed to fight against the enemy they perceive at least as threatening as ISIS; and they do not receive the weapons they need. Such a program is indeed set up for failure. There are enough capable and motivated fighters in Syria, but they need weapons that the U.S. is unwilling to supply them with.

Argument: The only de facto alternative to the Assad regime today is ISIS and other radical Islamist groups. The moderate opposition is too weak to constitute a real alternative to the Assad regime, or to destroy ISIS.

Response: I do not understand which information this argument is based on: the Free Syrian Army, together with other rebel groups, which are conservative but not extreme, are the only ones successfully fighting against ISIS. This has long been the case and is still true today. The situation in Idlib and Aleppo would otherwise look very different today, just like in many other towns in the region. These groups are fighting ISIS and Assad simultaneously. They need support, but they barely receive any attention in the U.S. and European discourse. If they do, they are portrayed as incapable and de facto irrelevant. In reality they are the only serious force on the ground that has successfully countered ISIS and continues to do so.

It is true that Islamic groups are strong, but most Syrians still support conservative, non-extremist groups. The West portrays ISIS to be so powerful because it knows how to attract publicity. ISIS caters to our common expectations, namely that Islamist groups are particularly cruel. It knows its Western audience very well and has made sure to carefully craft its image. The photographs showing at least 11,000 Syrians tortured to death in regime prisons revealed by “Caesar” prove that dying at the hands of the regime is no more merciful, let alone being killed by its incendiary or barrel bombs.

All the other conservative groups fighting in Syria are difficult to comprehend or less spectacular, which is why they are belittled even though they are successfully countering ISIS. Ignoring them and repeating the simplistic and false dichotomy between ISIS and Assad makes it nearly impossible to develop a meaningful strategy.

Argument: There are justified concerns that Assad’s fall under the wrong circumstances would not bring stability but even more chaos, displacement and extremism, as ISIS or other Islamist terrorists took over Damascus. This could also leave Syria’s minorities unprotected.

Response: This is possible. But we should remember that the Assad regime has long provided a fertile ground for extremism and massacres, and that they become increasingly frequent the longer the killing spree continues. Let me provide some examples:

First, the regime has committed ethnic cleansing along the territory between Damascus and the coastline, such as in the Qalamun-region and in Houla, Baniyas, and Bayda. These massacres were all targeting Sunni civilians, which caused a particularly high percentage of women and children being killed.

Second, take a look at a local ceasefire deal recently negotiated by Iran: The town of Zabadani, which is originally Sunni, is thereby supposed to become Shiite through a population exchange with Fouar and Kafraya, which are originally Shiite. This prospect is highly disturbing. That being said, the regime has already broken the ceasefire tied to the population exchange, because it did not approve of Iran negotiating directly with the rebels. The population exchange along ethnic lines might therefore not actually take place.

Third, a pattern emerges when looking at the regime strategy applied in many cities with a high percentage of religious minorities, such as Druse, Ismailis and Christians. Take for example Sweida, Masyaf, Salamiya, and Maaloula: in all these places the regime now tries to force men to serve in the military simply because they are running out of fighters. Many of those men refuse to die for Assad’s attempt to cling to power. Instead, they want to stay in order to defend their homes, their families and the clans, if need be. The regime has withdrawn its heavy weapons from all these places to communicate that it will not protect them any longer. This way the regime intentionally invokes further sectarianism along confessional lines. It is not the bastion for the protection of minorities that it claims to be. Quite the opposite: It puts the life of minorities on the line as part of its own survival strategy.

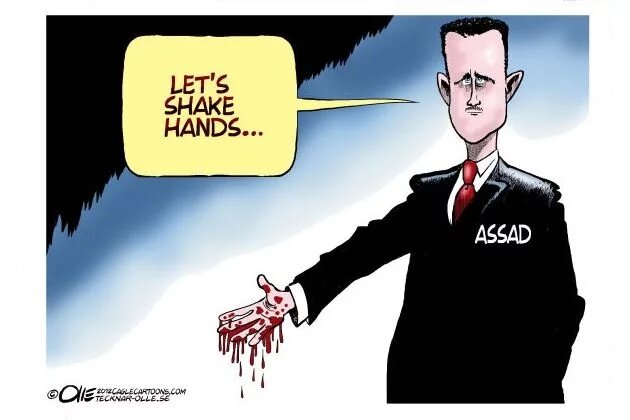

It would be cynical for the West to claim that it decided to tolerate Assad in order to prevent massacres of civilians, and in particular of religious or ethnic minorities. The over 20 well-documented massacres of Sunnis committed by the regime and its paramilitary henchmen would thereby basically be sanctioned. Assad is using Syria’s minorities, and the West risks using them too as an instrument to justify its own inaction. There is a Sunni majority in Syria, and you need to have them on your side if you want to successfully counter ISIS. That is why it is so important to communicate to Syria’s Sunni population that their life is worth just as much as the life of Syria’s minorities.

Argument: Removing Assad from power remains the right long-term goal but it needs to be part of a controlled transition phase that prevents the complete collapse of the state and includes as many Syrian groups as possible. To this end we need to negotiate with the Assad regime.

Response: Insisting that Assad must go should not be equated with dissolving Syria’s state institutions. They will not fall apart only because Assad is gone. That being said: Syria’s state institutions are already pretty instable with Assad in power and will continue to disintegrate if he remains in power. Today’s Syria is de facto a country split into four zones: the Kurdish region, the ISIS-held territories, the regime-held territories and the rebel-held territories. Only very few people ask for this status quo to be formalized. Considerably more people prefer some kind of confederation. But such a scenario becomes increasingly unlikely the more the rebel-held territories are reduced to rubble, and the less trust there is amongst regime-supporters that a solution acceptable for them can be found.

Argument: Unilateral military engagement by the U.S. with the goal of removing Assad bears uncalculated risks for escalation. The conditions and prospect of success are just as bad today as they were three years ago.

Response: Since 2011, the West has time and again decided not to intervene to stop Assad’s mass slaughter because „it could potentially make things worse“. Over the past four and a half years we witnessed the situation constantly getting worse without any meaningful intervention. At this point, gloomy predictions of things getting much worse are quite bizarre.

Over the past few weeks, many German newspapers have pleaded for a No-Fly-Zone because most of the deaths in Syria are caused by the regime’s air raids. The regime’s attacks from the air are also the most important reason for people to flee.

One point I would agree with concerns the fact that Russia has now created facts on the ground that make a No-Fly-Zone in southern Syria nearly impossible. In my view a credible threat of force, and shooting down a single regime helicopter over Aleppo, would have gone a long way towards deterring Assad. The fact that the West signaled from the outset that it did not want to intervene was interpreted by Assad as a carte blanche for applying any measure at his disposal to crack down on dissent. Now we find ourselves confronted with Russian air raid defenses. Needless to say, no one wants to risk an open armed conflict with Russia. The situation we find ourselves in today is in a way a self-inflicted problem.

Argument: Russia and Iran are prepared to protect their strategic interests in Syria by continuing to invest money, weapons, troops, and political capital. But the Syrian regime has turned into a costly burden for them and they are no longer fixated on Assad personally.

Response: Russia and Iran are undoubtedly capable of disrupting and interfering in Syria. But just as important is the fact that their resources and their will do not suffice to turn the page in Assad’s favor. Assad is not submissively dependent on them. He continues to do as he pleases, often to Russia’s and Iran’s detriment, for example with regard to the recent local ceasefire deal between Iran and the Syrian rebels, or with regard to the chemical and chlorine attacks.

Even if the West could agree with Iran and Russia on the future of Assad, this would not get us much further to a solution on the ground. For both Iran and Russia, their interests take precedent over a solution to the conflict. If Russia were seriously interested in a solution, why would it not channel its efforts through the United Nations? Russia is not interested in cooperation- it wants to show the U.S. and the world that it has the power to tip the scale unilaterally. Interestingly enough, Russia and Iran back the same side in Syria, but they do not have the same interests. They are in fact competitors. Russia tries to achieve its objective through military strength. Iran puts much more emphasis on strategic maneuvers, for example by getting rid of certain people who stand in the way between them and Assad.

Both can imagine a future without Assad- and this could indeed be a starting point. But where should the discussions go from there? The Iran nuclear deal has created a new situation with increasing potential for conflict between Russia and Iran, for example with regard to competition over oil exports. That is why Syria is part of the bilateral Russian-Iranian skirmish. I doubt that the West can offer something to satisfy both of their interests. And we have not even mentioned the fact that Iran and the Assad regime want to strengthen Hezbollah’s position and protect their access to weapons. Under no circumstances would they give up this objective considering how massively Hezbollah has supported the Assad regime in Syria. Given how many Hezbollah fighters have lost their lives in Syria, and given the fact that Hezbollah has literally secured the regime’s survival, Iran and the Assad regime will not budge on this point. Is the U.S. really prepared to go so far against the interests of its regional allies?

Argument: Pacifying Syria will only be possible if a compromise can be found between all external powers involved in the conflict – including Saudi Arabia, the Gulf States, Iran, and Russia. This is going to be an extremely difficult endeavor with unclear results, but the U.S. should nevertheless initiate such a diplomatic effort.

Response: The regional powers certainly need to be included in the search for an end to the war in Syria. It is laudable that the nuclear agreement with Iran has allowed the United States to take the whole spectrum of diplomatic possibilities into account. But it seems to me that so far no answers have been found to the following critical questions: what is the individual objective of the different powers in Syria, and how is it possible to reconcile these contrary interests, including those of Russia and Iran, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey? Which strategy does the West want to pursue other than talking to Assad and bringing the regional powers to the negotiating table? Will we really be prepared to invest our own resources in the regime’s survival? Or will we quietly allow Russia and Iran to do so? Assad has lost 60 to 80 percent of the Syrian territory because he could not defend it despite massive support from his allies. Even if Russia now sends troops to support him, they will not be sufficient to recapture and hold the lost territory.

It is critical for any diplomatic solution in Syria to take into account inner-Syrian forces. Currently the impression is created that this would be achievable if only we agreed to talk to Assad. But if one asks how the West plans to make sure that different Syrian groups will be included in the negotiations and in reconstructing the country, the answer is usually silence.

The article was translated and edited by Charlotte Beck, Program Director for Foreign & Security Policy at hbs North America