Remembrance cultures are more complex and diverse than a mere look at state-carried, nationalist commemorative practices might show. This complexity is present in and around Ypres.

Download Article

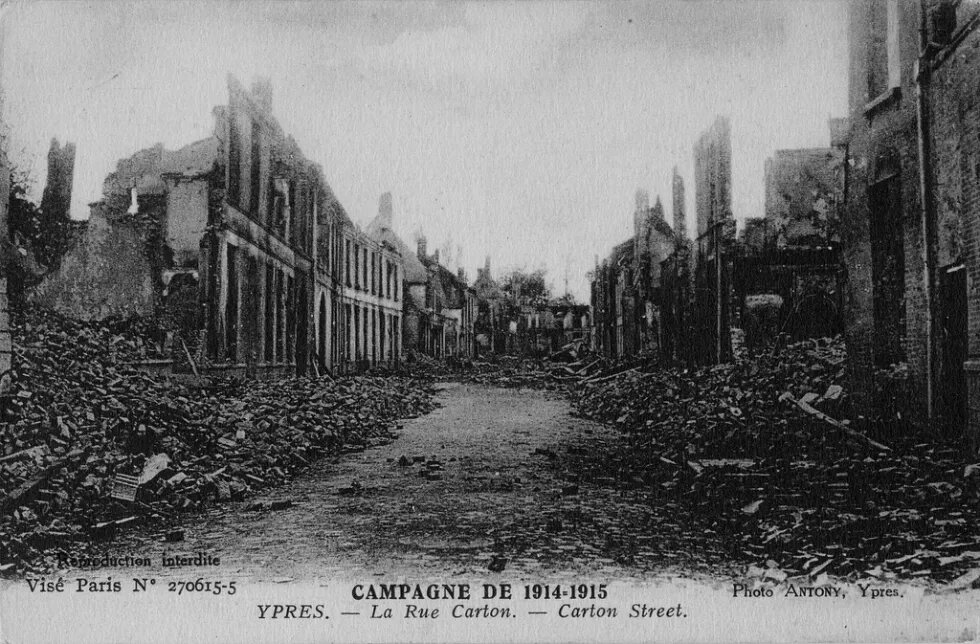

Coming from Passendaele along the N332, one enters the Belgian town of Ypres by passing under the Menin Gate. Towering over the moat of the 17th Century Vauban ramparts, the gate is located at the eastern exit of the town, marking one of the points where Allied soldiers of the First World War started out their burdensome marches to the shell-cratered front lines. The gate epitomises how Britain and the British Commonwealth commemorate their soldiers who died in the Great War. In its quiet imperial grandeur, the Menin Gate honours the memory of the soldiers who did not come back from the fighting. Under the gate, on white stone panels, are listed the names of 54,896 Commonwealth soldiers who died in the Ypres Salient but whose bodies were never identified or found. Thus the memorial gate exemplifies the intention of the British Empire to commemorate all those who died in individual manner. While soldiers whose remains were found and identified were buried under uniform but individual headstones on military cemeteries, the names of unidentified fallen soldiers were listed on memorials such as the Menin Gate and Tyne Cot Memorial. Bereaved families thus were offered sites where they could mourn their fallen relatives. At the same time, memorials such as the Menin Gate projected a more overarching meaning onto the massive-scale death caused by the war. The gate’s architectural design and inscriptions such as “Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam" and “Pro Patria, pro Rege” indicate how British remembrance culture invoked elements of a religious and imperial idiom, linking the death of soldiers to themes of patriotic sacrifice for freedom. This symbolism has not disappeared from British memorial culture. In Ypres it is quite palpable, for instance on Remembrance Day in November, when formal ceremonies are held and a Poppy Parade marches through the town. Given the importance of the Ypres Salient in the British Empire’s war effort and the central place of the Flanders Fields trope in Commonwealth memorial culture, it should not surprise that British remembrance practices today are the most visible in Ypres and its surroundings (in Belgium known as the southern Westhoek). Traces of other national remembrance traditions are, of course, also present in and around the town, but they remain less conspicuous than the British. The French Army, not as active in the Westhoek as the British forces, left a number of – mostly patriotic – mementos, such as the memorial overlooking the gentle slopes of the Kemmelberg. Having lost the war, German presence in the memorial landscape of Flanders Fields is more complex. Not only have the many smaller German war cemeteries been concentrated into four larger ones, Germany’s military graveyards are more sombre and dark in their outlook than the British sites. Tourists, nonetheless, easily find their way to these German cemeteries, not in the least to the one in Vladslo, where Käthe Kollwitz’ statues of mourning parents overlook the many silent graves.

Memorials such as the Menin Gate and the many military monuments are elements of national cultures of remembrance. They indicate how nation-states have been instrumental in shaping the way in which the First World War has been remembered throughout the 20th Century. Through commemorative practices they tried to honour the immense loss of life which had occurred in the name of Nation and Empire. More generally, historical narratives about violent pasts have always been useful instruments for politicians to legitimise existing orders, or to try and forge national identities. Remembrance cultures, however, are more complex and diverse than a mere look at state-carried, nationalist commemorative practices might show. This complexity is also present in and around Ypres. Other actors than nation-states, and other inspirations than patriotism, are – and always have been – active in shaping how the war is remembered. In Ypres remembrance of the war of 14-18 has strong local roots. Beyond strictly family-centred ways of remembering, particularly in the first decades after the war, both citizens’ groups and local authorities have engaged in their own way with the violent history of the region.

In the 1970s young people in and around Ypres started to take an interest in the war experiences and memories of elderly people in their families and villages. The idea grew to collect their testimonials in a book, a local people’s history of sorts, which was later used to stage a play in one of the villages south of Ypres. These initiatives, by telling the stories of the people who had lived through the First World War, were important in shaping a very local remembrance culture. This culture would profoundly influence how, in the following decades, the war was to be remembered in Ypres. The In Flanders Fields Museum (IFFM), which opened in 1998, chose a similar perspective. The central idea of the museum is that war is a reality experienced primarily by people – soldiers and civilians alike. By telling local and individual stories, the museum not only transcends national narratives of allies and enemies, but also succeeds in being relevant both at a local and a cosmopolitan level. Throughout the museum tour, the visitor is not provided with an explicit moral lesson. This does not mean, however, that the museum avoids morality. On the contrary: the problematic morality of war is brought to the foreground precisely by presenting war as a human reality. The museum is arranged in such a way that it encourages many visitors to pose moral questions about war. Thus they can also be incited to reflect upon peace. This is why many people leave the museum with the feeling that they have visited a peace museum, although the museum nowhere mentions peace as such, or advances an explicit message of peace. The IFFM even makes a conscious effort not to profile itself as a peace museum, but believes that by talking about war, people will start thinking about the meaning of peace. An effort to highlight ‘peace’ as the most important legacy of the First World War is more explicitly promoted by the local government of Ypres. Since the 1980s and 1990s, the city of Ypres has begun profiling itself as a ‘City of Peace’. A ‘peace official’ was appointed to coordinate various peace initiatives, such as a Peace Prize. The province of West-Flanders joined this peace-oriented strand in war remembrance. In 2002, the province decided to coordinate its tourist, cultural and educational WWI efforts under the banner of ‘War and peace in the Westhoek’. The underlying idea is that “what actually remains of the Great War in this region is the idea of peace” and “the unrelenting search for peace”. (2)

Why did I dwell rather extensively on remembrance practices in and around Ypres? First because it shows Ypres as a microcosm of WWI commemoration, an international contact zone where different remembrance cultures co-exist – mostly peacefully, though not without a certain degree of ambiguity in their underlying messages. Thus this short overview offers a first insight in the politics of war memory. Indeed, we cannot get a serious grasp of war remembrance without understanding its political and cultural diversity. Commemoration is not the privilege of one actor. On the contrary, from nation-states to local authorities and small-scale remembrance groups, a number of actors are engaged in war commemorations. And, no less importantly, all these actors have their own voice. This results in a multitude of different messages and undertones, from patriotic tropes of heroic sacrifice over the fight for freedom, to critical reflections on the problematic morality of war and calls for reconciliation and peace. A second reason why this micro-study of WWI commemoration in Ypres might be insightful, is that it gives a first hint to what seems to be missing in WWI remembrance. “Where is Europe”? In the run-up to the 2014-2018 centenary, the question has been put forward by Piet Chielens, the coordinator of the In Flanders Fields Museum. In Ypres, as in other WWI memorial sites, remembrance clearly is international, as different nations and cultures come to the town to remember their war histories. At the European level, nonetheless, initiatives to commemorate the war at the moment seem to be missing. The absence of the European Union is striking, Chielens argues, because after the Second World War it was Europe who provided the answer to the problem of war and peace on the continent. (3)

This is an interesting observation. It challenges us to reflect upon the role of Europe in the commemoration of WWI. In this essay I want to take up this reflection, and review the possibility of a European sphere for the remembrance of the First World War, maybe even of a ‘shared’ European commemoration of that war. Based on my introduction of how the war is remembered in Ypres, these reflections are guided by the question whether the town’s remembrance culture might serve as a source of inspiration in this quest. (A third reason for discussing it at some length.) What might Europe learn from the ‘Ypres way of remembering’ the war of 14-18? ‘Peace’ as the legacy of war clearly is one of the voices to be heard in Ypres. Is this a fruitful point of departure for a European commemoration of WWI? Might peace be the unifying theme around which the EU could build a shared remembrance of the First World War? One could argue it is, as it can easily be linked to existing narratives on Europe as a ‘peace project’ and a solution to the continent’s centuries’ old problem of war and bitter rivalry. My suggestion, however, is that this link, how tempting it may sound, is not as self-evident as it might seem at first sight. Although I believe it would be meaningful and relevant for the EU to take up a ‘peace-oriented’ European commemoration of WWI, it is important that such a commemoration does not result in gratuitous formulas. These will only lead to pertinent and legitimate criticisms, for instance on the part of historians. Therefore, a thorough reflection on the critical preconditions of the idea is necessary. This is what I want to do in this essay. Two questions guide me in this endeavour. First, although remembrance and history both work with the past, they are not the same. Because commemorations are political, also when they foreground peace, tensions might arise with the historian’s reading of the past. How do these tensions play out? Can we avoid mythologising Europe’s past when we promote peace-oriented remembrance? And, second, how would a European commemoration of the First World War relate to other remembrance traditions? As my sketch of Ypres as a site of memory indicates, WWI remembrance comes in many shapes and forms. If we want to take this plurality seriously, it is necessary to ponder on how a peace-oriented commemoration at the European level would relate to other WWI memorial narratives. Let us, however, start out with looking at the suggestion of linking a peace-oriented commemoration of WWI to existing narratives of the EU as a ‘peace project’.

War & peace in Europe: memory, myth, history

The European Union is about peace. The Union is peace. These catchphrases sound familiar, not in the least because European leaders tend to reiterate them time and again in official declarations, in dinner speeches at summits, and at press conferences aimed at increasingly sceptical domestic audiences. In 2012, the idea that European integration and peace are intimately linked was formally sanctioned by the Nobel Peace Prize committee. Even the most cursory glance at speeches and declarations by the EU’s leading politicians, and, indeed, at the 2012 Nobel Peace Prize announcement, makes clear that memory plays a crucial role in this EU – peace nexus. (4) More specifically, it is the memory of the Second World War that functions as a constitutive element in discourses about the origins of the Union, as well as in the collective identity the EU seeks to promote. In these discourses Europe appears as the phoenix arising from the ashes of the Second World War. While the 2012 Nobel Peace Prize announcement stated that “The dreadful suffering in WWII demonstrated the need for a new Europe” (5) , the preamble of the Constitutional Treaty of the EU solemnly reads that the peoples of Europe, “reunited after bitter experiences”, are “determined to transcend their former divisions”. That these experiences and divisions refer to WWII becomes clear if we look at the official history represented on the EU’s website, where the history of the EU starts in 1945-1949. Under the heading “A peaceful Europe – the beginnings of cooperation”, one reads that “The EU is set up with the aim of ending the frequent and bloody wars between neighbours, which culminated in the Second World War”. (6) That the EU officially links its origins to the aftermath of WWII and to peace is also reflected in the fact that the Union has designated 9 May 1950 as the official Europe Day. That date commemorates the Schuman Declaration which led to the European Coal and Steel Community, the first step in Franco-German reconciliation. As Fabrice Larat notes, this particular interpretation of Europe’s history, which in effect seeks to identify a historical necessity for its unification, constitutes something of an Acquis Historique Communautaire. (7) Like the accumulated legislation, legal acts and court decisions forming the body of European Union law, this acquis historique has to be underwritten by all newcomers to the Union.

All in all, this official history of the EU seems to have been successful in establishing in European public consciousness the triadic link between the memory of WWII, European integration and peace. Now, if our ambition would be to transpose to the European sphere the ‘peace-oriented’ way of remembering WWI we encountered in Ypres, at this point we might be tempted to take the obvious path and argue for broadening this official history of the EU’s origins explicitly to the First World War. Commemoration of WWI at the European level would thus be linked to existing narratives about peace as the main legacy of Europe’s war-torn history and the reason why Europeans opted for unification. In this scenario, the war of 14-18 could be commemorated as an episode in a wider European civil war, a modern Thirty Years’ War, which nearly brought Europe to its knees, but which ultimately showed Europeans the road to peace through unification. The First World War as one of the bitter and divisive experiences from which Europeans drew the high-priced lesson of the value of peace. Tempting as this may sound, however, some caution is warranted. Numerous historians and social scientists have voiced critical remarks about the EU’s official history. In their view, this history all too easily links the idea the origins of the European project to peace and the experience of war. They are, moreover, on their guard when the past is inconsiderately interpreted in function of the present and used for political purposes. One of the crucial issues at play here, besides obvious suspicions about political instrumentalisations of history, is the concern that commemorations, however legitimate and valuable they may be, risk mythologising the past, thus obscuring our historical understanding of that past.

In light of the purposes of this essay, it seems perilous to proceed without at least engaging these critiques. Let us therefore consider the critique that the EU’s official history presents a mythologised reading of the origins of European unification. To be clear, myths should not be viewed as entirely false narratives about the past which are in urgent need of critical deconstruction and falsification on the basis of the historical record. The issue is somewhat more complex. As British historian Lucy Riall phrases it in her impressive study on the invention of the hero Garibaldi, successful myths are neither genuine nor invented, but a compelling blend of both. They are neither spontaneous nor imposed, but can far better be characterised as an intricate process of negotiation between actors and audiences. (8) Myths should thus not be understood in the sense of fictions, or fairy-tales. Nonetheless, a sceptical stance is justified. Myths may not necessarily be a lie or a fiction, but they do tend to leave out a lot of history – all too often too much history. And this is an important observation, not in the least because myths are socially functional in the sense that they serve to enhance collective identities (e.g. of the nation), and are often used to legitimate political decisions. (9) Therefore, as Stuart Hall has noted, we should resist the temptation to go along too easily with foundational myths. Indeed, in the case of Europe, they might license Europeans to disavow not only the historic instability of their history, but also their deep inter-connections with others’ histories. Hall emphatically stresses we must beware lest the disconcerting discontinuities, brutal ruptures, grim inequalities and unforeseen contingencies of Europe’s real history are bound “into the telos of a consoling circular narrative whose end is already foreshadowed by its beginning”. (10) With regards to the post-war European integration project, such a consoling narrative might sound like this: Yes, Europe knew its bitter rivalries, and as Europeans we fought out gruesome wars, but in the end everything turned out quite fine: we learned from our mistakes, and out of these wars a desire for peace was born which gave rise to European unification, so that now Europe, as a beacon of light, is a force for good in the world. Although there definitively is truth to this narrative, it also leaves out a lot and creates blind spots. Not only in terms of the present political situation (are the EU and its Member States indeed that peaceful, for example in their external relations?), but also in terms of the historical record of the European project.

Without going into too much detail, it is useful to take a closer look at how historians and social scientists have deconstructed the EU’s official narrative of ‘Europe born out of the World War as a peace project’. Some scholars see Europe as a purely economic project. Others have argued that the origins of the EU are not linked to economics or to the rise of new ideas about peace through cooperation, but to classic realpolitik considerations. Sebastian Rosato for example claims that the making of the European Community in the early 1950s is best understood as an attempt by the major West European states, and especially France and Germany, to balance not only against one another, but also against the Soviet Union. In light of this explanation, it should not surprise that Joseph Stalin comes into view as “the true federator of Western Europe”. (11) This image may be a witticism, but it does make good historical sense to point to the early Cold War as a driving force behind the integration of Western Europe. In official EU historiography, the Cold War is largely absent, unless it is presented as an abnormal situation which was eventually overcome by the integration of Eastern European countries in the Union after the fall of the Berlin Wall. (12) When we revisit the history of the early Cold War, however, a more complex view emerges. It is interesting, for instance, to highlight the role of the US in European integration. In the late 1940s, the Americans were in favour of European unification. During the preparations of the Marshall Plan, the US pushed the idea of economic and political unification of Western Europe (even of a United States of Europe). This, however, met with serious resistance of European governments, who were anxious about surrendering national sovereignty, and not always that keen on close cooperation with Germany. (13) It was in this context that the more pragmatic concept of integration came to the fore as, in the phrasing of Bo Stråth, “the palliative” to avoid a deadlock situation in the relationship between the US and Western Europe. Stråth’s reflections on the origins of European integration are interesting in another respect as well. He points to the fact that at this stage, the aim of the founding fathers of the European project (Schuman, Adenauer, de Gasperi) was not necessarily to create a democratic organization, but rather to establish a system of protection that would not only make their nation states safe from each other, but also from populist forces in democracy. Recent history, in particular the rise of the Nazis and fascists, had revealed the dangers deeply embedded in democracy, and shown how easily the rule of the people could be abused. In light of these experiences, they created a High Authority (the forerunner of the Commission) as an expression of centralized power, shielded against the whims of public opinion. Again, the EU’s official history seems to remain silent about this side of the project’s origins. And this is not without its consequences. (14) When confronted with claims for more democracy in Europe today, the teleology of the EU’s official history may sound somewhat awkward, in the sense that it draws out a linear continuity of the current European project with the plans of these founding fathers, in which the High Authority/Commission and not the Parliament played the key role. The official historiography of Monnet, Schuman and Adenauer as the founding fathers of Europe, moreover, shuts out a lot of interesting interwar history. After WWI, interest in the idea of a common Europe was widespread. In 1929, the French Minister of Foreign Affairs Aristide Briand, who in 1926 had received the Nobel Peace Prize together with Gustav Stresemann, formulated a plan for a European Union. (15) At around the same time membership of Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi’s Paneuropean Union grew to approximately 20.000 across Europe. (16) This inter-war history of the ideas for a peace-minded Europe is interesting, not only because it points to the very diverse roots of these ideas, but also because in light of the upcoming doom of the Second World War, they failed. Thus, this history shows how the European idea developed in a non-linear way. It also shows the fragility and contestability of peace-oriented political projects. And, importantly, the history of the road to WWII and the fight against Nazism sparks interesting questions for pacifists: when is violence legitimate and needed? In other words, ‘peace’ appears as a complex notion, and not as an easy-to-embrace formula.

Histories of war, reflections on peace

If we take these critical readings seriously, we should be sceptical vis-à-vis some of the more mythical underpinnings of the EU’s official history. Instead of promoting a linear and unifying memory of European integration as a peace project, it seems more fruitful to advocate openness to historical context. Thus we leave room to explore different and maybe competing narratives of the origins of the European idea. We avoid, in the words of Tony Judt, building Europe upon shifting historical sands. (17) These insights are also relevant for the exercise central to this essay. If we want to transpose the peace-oriented commemoration of the First World War we encountered in Ypres to the European level, it makes little sense to do this in a manner which would pave the way for yet another official narrative negligent of historical complexity. We do not need another myth. What complicates matters further is that the risk of creating myths also exists in pacifist commemorations of WWI. Again, a look at remembrance in Ypres and Flanders makes this clear. In the Flemish public imagination, remembrance of WWI is almost naturally linked with the idea that peace is the main legacy of the war. The catchphrase ‘No More War’ is omnipresent in Flemish remembrance culture. Historians, however, have repeatedly voiced their concern over the matter-of-course manner in which commemoration in Flanders establishes a link between WWI and peace. In particular they seem concerned that commemorations tend to promote a public understanding of the war as ‘senseless’. Insisting too strongly on the trope of the senselessness of the Great War and peace as the main lesson, they claim, tends to obscure our understanding of the historical reality of the war. For many contemporary Belgians, the war was neither senseless nor absurd. On the contrary, many Belgians seem to have been motivated by patriotism and the will to defend family and fatherland against the brutal aggressor. Moreover, peace-oriented commemorations tend to ignore that numerous soldiers were not only victims, but also perpetrators, and that many were also fascinated with war and violence. Without taking this fascination into account, we cannot fully understand the First World War. (18) That pacifist readings of the First World War risk yielding mythicised histories that are closed, predictable, and at bottom a-historical, is underlined by Ann-Louise Shapiro in her study of French schoolbooks on WWI. In her view, pacifist rewritings of French handbooks in the 1920s and the 1990s resulted in readings which presented European history as the unfolding of an inevitable process and the fulfilling of a destiny: peace. For Shapiro, this constitutes a unitary and a-historical account of European history. It flattens alternative trends and possibilities, and suppresses discontinuities which are, by contrast, deeply threaded through the past. History, Shapiro emphasises, works better if it has eye for contestation and contingency, and if is attuned to the multiplicities of the past and the differences among historical actors. (19)

To be sure, these critiques of the mythologising effects of official historiographies and pacifist rewritings of history make clear that the idea of promoting ‘peace’ as the unifying theme of a European commemoration of WWI turns out to be more complicated than it might have seemed at first sight. Thus we are urged to recast the central question of our endeavour: Is it possible to think of a peace-oriented commemoration of WWI that does not mythologise the past, but remains open for the complexities of history? How might such a war commemoration look like? Could it – at the same time – hold critical potential, while also being attuned to the multiplicities of history? To find a possible answer to these questions, I suggest looking again to Ypres for inspiration. In particular, I suggest looking at the historical methodology underpinning the In Flanders Fields Museum. As I noted in the introduction, the story-line of the museum does not explicitly departs from a political or moral message. The narrative of the museum, on the contrary, starts out from the history of the war, specifically focusing on the daily life experiences of soldiers and civilians in war time. These experiences are presented in their historical context, so that attention is paid not only to the consequences of the war (the suffering of soldiers and citizens), but also to its causes. Particular attention, moreover, is paid to the landscapes in which the war was fought. The museum thus presents the war from a cultural and social-geographical perspective. In other words, if offers a historical reading that foregrounds the human reality of the war. Interestingly, this is where the museum starts to develop its moral and political potential. Although the museum is not intended to be a peace museum, through presenting war as a human reality, visitors are shown its problematic morality. Many visitors are thus encouraged to pose moral questions, and to critically reflect upon the meaning of war. And while the IFFM makes a conscious effort not to highlight ‘peace’ as a theme, the organisers believe that by talking about war, people will also start thinking about peace.

This methodology is interesting, and promising. If offers a logic which brings the past into the present, while avoiding to instrumentalise that past in function of present-day objectives. Starting out from a historical reading of the violent past, it leads to a critical and moral reflection, not only upon the violent past itself, but also upon conflicts and violence in the present. Reading the past critically encourages a critical reading of contemporary politics. In other words, this methodology presents the violent past not only as a source of historical knowledge, but also as an occasion for a broader critical reflection upon war and peace. The idea of peace, in all its complexity, emerges out of Europe’s conscience troubled by its violent history. At the same time, this way of approaching and presenting the past remains open to the complexities and ambiguities of history. There is ample space for looking at various aspects of war history, and for opening different stories about the war. It is recognised that history can only show its emancipatory potential if its contingent character is respected, and if historical narratives are multi- rather than uni-vocal. Teleological and unifying narratives, which silence alternative histories and comfortably justify the status quo, are avoided. Although history is linked to present-day themes, the risk of approaching the past in a one-sided or mythologising way is reduced. On the contrary, to make a critical reflection upon the past possible in the first place, it is necessary that as many stories as possible are told about the war. This approach, for example, gives the many stories about the multicultural and colonial aspects of the First World War, which for decades were pushed aside in traditional nationalistic and patriotic narratives, the full attention they deserve.

My suggestion therefore is that if our ambition is to promote a peace-oriented commemoration of WWI at the European level, we should start out from this methodology of bringing the past to the present. It offers the possibility of a European commemoration of the First World War which foregrounds the idea of peace, while the risk of mythologising the past is mitigated. This is, however, not the end of our enquiries. In remembrance practices of the First World War, the voice of ‘peace’ is only one among many. The reality is that commemoration of WWI in Europe is characterised by a multitude of national and local traditions. How does this plurality reflect on the project of a European peace-oriented commemoration of the war of 14-18?

A pluralism of war memories

Europe’s violent 20th century history has produced a plurality of memories, often of a bitter and divisive nature. This is clearly the case for the Second World War. But as my sketch of commemorative practices in and around Ypres indicated, remembrance of the First World War equally comes in many shapes and forms. Different actors are involved in remembrance practices (states, communal authorities, and local actors). And messages and underlying themes do not sound in unison, but in a variety of voices and tones. If we broaden our outlook from Flanders Fields to WWI commemoration in the whole of Europe, the picture becomes even more complex. A mere look at November 11, Remembrance Day, shows that on that day some countries (e.g. the UK, Belgium, France) commemorate their war dead, while others, mostly in Central and East Europe, celebrate their independence and national freedom. (20) In Europe, a number of countries have transformed the memory of the war into a token of peace and reconciliation. In Belgium the ‘peace idea’ is very present. Even the Army uses the catchphrase “remembering is keeping the peace”. In Ireland, remembrance of WWI was reframed to underline reconciliation between Catholics and Protestants. And the iconic image of Mitterrand and Kohl holding hands in Verdun constitutes one of the main symbols in Franco-German reconciliation. In other countries, the situation is somewhat different. As we have seen in Ypres, official British remembrance of WWI traditionally has had patriotic and militaristic undertones. That this way of remembering the world wars also has political significance is shown by Anne Deighton who argues that ‘imperial memories’ have influenced post-war UK foreign policy, including the British stance towards European integration. (21) In other countries, such as Hungary, memories of the First World War, in particular of the peace treaty of Trianon of 1922, are still acted out in public imagination. (22) And, importantly, as most of the countries involved in WWI were colonial empires, there is a wide variety of post-colonial memories of the war, which until recently were kept in the shadows of most nations’ remembrance cultures.

What does this mean? That at the moment, there simply is no ‘shared’ memory of WWI in Europe. Different remembrance traditions exist next to each other. If the ambition would be to have a European peace-oriented commemoration of WWI, how then to proceed? As a first option, we might hope that under the impact of further European integration national memories will be transformed and reconstructed (although not entirely substituted) by layers of a transnational peace-oriented European memory. (23) It seems, however, that this process, at least as far as WWI is concerned, is only in its very early stages. And, what is more important, above we learned that efforts to promote such a ‘shared’, consensual memory might result in mythologising, a-historical readings of the past. The violent past is a source of divergent interpretations, not of easy consensus. In thinking about peace-oriented war remembrance, we therefore need to take this plurality seriously. This is all the more true if we recognise that plurality and difference might be regarded as integral parts of peace. Foregrounding the idea of peace in commemoration then does not only mean talking about the problematic morality of war and violence. It also means recognising that people remember the violent past in many different ways. In other words, acknowledging difference becomes one of the cornerstones of a peaceful memorial policy. Here it is useful to note that this exercise at times can be conflictual. How valuable it might be to try and find common positions in war commemorations (e.g. when we want to create monuments and museums, or jointly write school books) (24), I agree with Duncan Bell when he writes that “a focus on the necessarily conflictual nature of historical interpretation provides the first step in creating a political environment in which different group identities can co-exist peacefully.” (25) Diversity in memorial culture indeed sometimes manifests itself in a dissonant and contentious manner. A peaceful and pluralist remembrance culture should leave room for these possible conflicts and dissonances. (26) At the same time, it is important to note that this pluralist approach to war commemoration does not imply relativism, in a moral nor a historical sense. In an atmosphere of open dialogue, it should always be possible to enter into critical discussions on the moral implications of different forms of war commemoration. A similar critical discussion is possible about the historical value of various memorialisations, as not all remembrance narratives are equally valid in light of state-of-the-art historiographical debates.

From Ypres to Brussels?

What, now, are the chances of such a peace-oriented commemoration of WWI at the European level? Given the many remembrance traditions that highlight other themes than peace, some member states may be reluctant to support the idea. On the other hand, as we have seen, ‘peace’ already plays an important part in the acquis communautaire historique of the EU. This might facilitate the idea. In any case, based on the above, it seems that if we want to start talking about the possibility of a European remembrance of WWI centred on peace, this conversation will have to take place in the field of tension created by the plurality of war memories. This also means shying away from the temptation of promoting an easily-shared and ‘unifying’ but ultimately a-historical narrative, which inconsiderately links European unification, the memory of WWI and the idea of peace. All of this, admittedly, has remained largely theoretical. And although it was not my aim in this essay to come up with practical suggestions, the question of how the EU might proceed practically if it wants to sponsor a peace-oriented commemoration of WWI is relevant. Here, again, my answer will betray my background as historian. I would suggest, for example, that European commemoration efforts focus on projects where the history of 14-18 can be given a central place. One might think of historical expositions, war museums (as in Ypres), historical online platforms, conferences where historians engage in debate with the public, etcetera. These are all forums where the past can speak with more than one voice. And where audiences, through engaging with Europe’s violent history, can be inspired to critically reflect upon violence in the past as well as in the present.

Endnotes

(2) http://www.wo1.be/en/network.

(3) De Morgen, ‘Waar blijft Europa met de herdenking van WOI?’ [Where is Europe in the commemoration of WWI?], 3 Oktober 2013.

(4) Chiara Bottici (2010), ‘European identity and the politics of remembrance’, in Karin Tilmans, Frank Van Vree & Jay Winter (eds.), Performing the Past. Memory, History, and Identity in modern Europe, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, p. 335-359.

(5) http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/2012/press.html

(6) http://europa.eu/about-eu/eu-history/index_en.htm.

(7) Fabrice Larat (2005), ‘Presenting the Past: Political Narratives on European History and the Justification of EU Integration’, German Law Journal, 2(6), p. 287.

(8) Lucy Riall (2007), Garibaldi. Invention of a Hero, New Haven CT: Yale University Press, p. 392.

(9) More in Chiara Bottici (2009), ‘Myths of Europe: A Theoretical Approach’, Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society, 2(1), p. 9-33.

(10) Stuart Hall (2003), ‘“In But Not of Europe”: Europe and Its Myths’, in Luisa Passerini (ed.), Figures d’Europe. Images and Myths of Europe, Bruxelles: P.I.E.-Peter Lang, p. 38.

(11) Sebastian Rosato (2011), Europe United. Power Politics and the Making of the European Community, Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, p. 2-6.

(12) Fabrice Larat (2005), ‘Presenting the Past: Political Narratives on European History and the Justification of EU Integration’, German Law Journal, 2(6), p. 278-279

(13) Robert Gildea (2002), ‘Myth, memory and policy in France since 1945’, in Jan-Werner Müller (ed.), Memory & Power in Post-war Europe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 66.

(14) Bo Stråth (2005), ‘Methodological and Substantive Remarks on Myth, Memory and History in the Construction of a European Community’, German Law Journal, 2(6), p. 263 & 268.

(15) Pim De Boer (1997), Europa. De geschiedenis van een idee [Europe. The History of an Idea], Amsterdam: Prometheus, p. 125-126.

(16) Katiana Orluc (2000), Europe before Europe: The Transformation of European Consciousness after the First World War, p. 15 (www.helsinki.fi/hum/nordic/strath/archive/pastseminars/0001writing_history/seminar_writing_history.html).

(17) Tony Judt (2002), ‘The past is another country: myth and memory in post-war history’, in Jan-Werner Müller (ed.), Memory & Power in Post-war Europe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 182.

(18) See for example the debate ‘Commémorer 1914’ in Journal of Belgian History XLII, 2012, nr. 2.

(19) Ann-Louise Shapiro (1997), ‘Fixing History: Narratives of World War I in France’, History and Theory, 4(36), p. 129.

(20) See National 4 and 5 May committee (2014), Na de oorlog. Herdenken en vieren in Europa [After the War. Remembering and Celebrating in Europe] http://www.4en5mei.nl/english.

(21) Anne Deighton (2002), ‘The past in the present: British imperial memories and the European question’, in Jan-Werner Müller (ed.), Memory & Power in Post-war Europe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 100-120.

(22) Willfried Spohn (2005), ‘National Identities and Collective Memory in an Enlarged Europe’, in Klaus Eder & Willfried Spohn (eds.), Collective Memory and European Identity. The Effects of Integration and Enlargement, Aldershot: Ashgate, p. 9.

(23) Ibid., p. 4.

(24) See Siobhan Kattago (2011), Memory and Representation in Contemporary Europe: the Persistence of the Past, Burlington, VT: Ashgate, p. 10.

(25) Duncan Bell (2006), Memory, Trauma and World Politics. Reflections on the Relationship between Past and Present, London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 20.

(26) Theoretically, this links up to an agonistic conception of politics (see Chantal Mouffe (2013), Agonistics: Thinking the World Politically, London: Verso).