In the name of effectiveness, democracy and reforms, the Polish government pushes with radical measures to take control over the juidiciary power and slowly loses popular support.

At first glance it may seem that the ongoing international feud over the state of Polish democracy and judiciary has had no effect on the ruling party's political standing. But popular support for Law and Justice and its leader, although impressive, is far from solid.

Poland against Europe?

December 20th 2017 will go down in the history of the European Union. On that day the European Commission for the first time in history triggered Article 7 of the Lisbon Treaty. This probably second best known article of the Treaty – alongside Article 50, which the UK evoked to leave the Union – is a disciplinary measure now taken against the Polish right-wing government for violations of the rule of law and an assault on the independence of the judiciary.

Announcing the decision, Vice-President of the Commission, Frans Timmermans, said that the step was taken with a heavy heart”, but that after two years of verbal skirmishes between EU officials and various members of the Polish government, as well as procedural back and forth, ‘the Commission can only conclude that there is now a clear risk of a serious breach of the rule of law.’

The Commission is not the only European institution to condemn the political offensive begun by the Law and Justice [PiS] party soon after its double victory in both the presidential and parliamentary elections of 2015. A little over one month before, on 15th November, the European Parliament – which is another body entitled to evoke Article 7 – adopted a resolution in which it stated that the rule of law in Poland was under attack and ‘called on the Parliament's civil liberties committee to draw up a report on the situation in Poland, which would be the basis for a plenary vote later formally asking the [European] Council to activate Article 7. Eventually, the Parliament withdrew from the whole procedure, but only in order not to duplicate the actions already taken by the Commission.

The third major institution since long involved in the feud with the Polish government has been the Venice Commission, which is ‘a Council of Europe independent consultative body on issues of constitutional law, including the functioning of democratic institutions and fundamental rights, electoral law and constitutional justice.

Ironically, the Venice Commission was invited to investigate the situation in Poland by... the Polish government itself, more precisely by the then foreign minister Witold Waszczykowski. Waszczykowski – as it was explained by his spokesperson – wanted to clarify the controversies over the first stage of Law and Justice's judicial reforms aimed at the Constitutional Tribunal. At first cooperative, Polish officials soon grew tired of the VC's critical remarks on the ongoing legislative process and Waszczykowski – widely considered one of ‘the politically weakest ministers in the government‘ – was ousted in January 2018 by the new prime minister, Mateusz Morawiecki.

Despite a lack of cooperation on the Polish side, the VC continued working and in its latest report on Poland, published in December 2017, unequivocally stated what danger all the changes introduced to the judiciary pose to Polish democracy. For example, on the reform of the Supreme Court [not to be confused with the Constitutional Tribunal] the Venice Commission wrote that the proposed reform, if implemented, will not only threaten the independence of the judges of the SC, but also create a serious risk for the legal certainty and enable the President of the Republic to determine the composition of the chamber dealing with the politically particularly sensitive electoral cases.

Apart from highlighting the threats to the Polish legal order, many experts – both domestic and international – argued that the government's actions violate numerous articles of the Polish Constitution which regulates the status of many of the institutions the government reformed. With only a tiny majority of votes in the Sejm, the lower chamber of the Parliament, the ruling party was incapable of passing any amendments to the Constitution. It therefore decided to change it through regular acts of parliament while maintaining it had never been violated. But what exactly were the ‘reforms’ which caused such an uproar abroad?

Judicial ‘reforms’

The first stage of crisis began with Law and Justice's battle against the Constitutional Tribunal, a judicial body the main task of which is to analyse the compliance of statutory law with the Constitution of the Republic of Poland. The Tribunal is composed of 15 judges elected by the lower chamber of the Polish parliament on nine-year terms. Soon after the new government took over it announced that five judges nominated by the previous parliament right before the end of its term were elected too early and that the choice should be left to the incoming MPs. The Tribunal asked to solve the issue and stated that the procedure was indeed flawed but only in regard to two out of five judges concerned. However, the new president Andrzej Duda – formally independent but supported by PiS – refused to recognise the three remaining judges. Instead, a new parliamentary majority elected five new judges all of whom the president promptly swore in.

This action was a blatant breach of the Constitution which clearly states that all verdicts by the Tribunal are final and does not give the president any right to refuse swearing in judges properly elected by the parliament. Duda, although himself a lawyer and a former university lecturer, persisted. The stand-off continued for the next year until the term of the then president of the Tribunal, Andrzej Rzeplinski, came to an end. With Rzeplinski gone and a new president of the Tribunal appointed, the institution was immediately marginalised and bent to the will of the PiS leader, Jarosław Kaczyński.

Why did PiS decide to start a political war against one of the most important judicial institutions? As the Guardian journalist, Christian Davis, rightly explained: ‘Kaczyński’s attitude towards the Constitutional Tribunal may be rooted in his experience as prime minister in the mid-2000s, when the court inflicted a series of defeats on a short-lived PiS-led coalition government.’ Now, after only one year in power this obstacle had been removed. As a result, the opposition lost the way to challenge constitutionality of the reforms introduced by the ruling party. PiS's leader did not, however, intend to stop at this point.

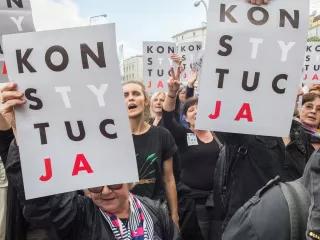

The second stage of the “reforms” targeted primarily two other institutions crucial to the whole legal system in Poland and judiciary independence: the Supreme Court and the National Judiciary Council [KRS]. These new proposals prompted significant social outburst and in July 2017 protest under the slogan “Free Courts” sprang all over Poland, not only in the biggest cities, traditionally more hostile to Law and Justice. The social unrest was ended quite abruptly by the president Duda's decision to veto two out of three new laws presented to him by the parliament. Duda announced he would present his own proposals in two months time. This decision caused uproar among some PiS supporters, and right-wing pundits struggled to explain the reasons behind president's decision.

However, those hoping for a radical change in policy towards judiciary were soon disappointed. New proposals presented by Duda in September 2017 retained the most controversial provisions. In case of the legislation regarding the Supreme Court the new law lowered the retirement age of judges from 70 to 65 years, which allows for an immediate removal of around 40 percent of the Court's 86 judges, including the First President of the court Małgorzata Gersdorf who turned 65 precisely in 2017. The new regulation stated the judges could stay on the job, if they were allowed to do so by the president himself. This, again, was a breach of the Polish Constitution which clearly states that the first president of the Supreme Court is sworn in by the president for a six-year term. In case of Gersdorf, the term ends only in 2020. By lowering the retirement age PiS wanted to reshuffle the composition of the SC, without actually changing the Constitution.

The same strategy was applied against the National Judiciary Council [KRS], the body responsible for – among others – making judicial appointments. Under the new law 15 out of its 25 members are to be nominated by the parliamentary majority. The only change Duda introduced to the bill was to increase the majority needed to elect a member of the KRS to three-fifths of the votes. The president argued this measure would force parties to compromise on their nominees as none of the parliamentary clubs has that many MP's at their disposal. This argument, however, is nullified by the fact that in case of any stalemate, the decision reverts to a simple majority. Given the fact that without the consent of Law and Justice no candidate could secure three-fifths of the votes, the new law handed the control over the Council to the ruling majority.

What is that for? The simplest answer to the question about the reasons behind all these measures is obviously the will to eliminate any possible checks the judiciary could place on the government's actions. In public communication however, both domestic and with international partners, Polish authorities came up with a set of different replies. Those explanations, though more elaborate, are hardly more credible. Let's go through and debunk them one by one.

The government explains

The main argument is effectiveness. The government – both under the previous PM Beata Szydło and now under Mateusz Morawiecki – argues that Poles demand the courts to work faster, be more transparent and tougher on corruption among the judges themselves.

It is undoubtedly true – as it was repeatedly confirmed in the polls – that most Poles would like the courts to do a better job in all these aspects. In the same way, however, one could ask the people if they wanted to have a better national health service or public transport. It's fair to assume most of them would, but this does not mean they would support every measure taken by the government to achieve this goal, especially if those measures involved breaching the Constitution.

Secondly, it is worth noting that even the radical measures taken by the current administration may not produce any of the promised results. By simply taking control over judiciary the government will not make it work faster and produce fairer results. Thirdly, when the government officials cite low approval rating of the judiciary among citizens, they are right. What they fail to acknowledge is the fact that approval ratings of elected politicians stand at even lower levels.

To the above charges, however, the party ideologues would probably answer that by exerting more political control over the judiciary the ruling party is making the courts... more democratic. This claim may seem paradoxical at first glance but becomes clear in light of the party's rhetoric. As German-American political scientist, Jan-Werner Mueller, convincingly argues in his best-selling book “What is populism?”, every populist movement is founded on a belief that they and only they represent the will of the People. PiS is no exception. Of course PiS representatives acknowledge the existence of opposition, yet they argue that it is animated by international forces, or ‘elites’ yearning to get their influence back.

From this perspective almost every action taken by the government is by definition legitimate – since the government represent the People – and every power grab makes the country more democratic as the administration acts only in the name of ordinary Poles. Thus, liberal principles of checks and balances as well as protecting the rights of minorities are being sacrificed in the name of unlimited democracy.

The third argument very often used by the governing party says the judicial system needs deep reform because it has never been ‘decommunised’ and that communist-era judges or their collaborators still exert an enormous influence on the judiciary. That was precisely the argument made by Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki in an op-ed published in the Washington Examiner, a rather marginal American conservative daily.

‘In the 1989 Roundtable Talks between Poland’s Communists and the democratic opposition, Morawiecki wrote, “then-president General Wojciech Jaruzelski – the man who ran Poland’s martial law government for the Soviets – was allowed to nominate an entirely new bench of communist-era judges to staff the post-communist courts. These judges dominated our judiciary for the next quarter century. Some remain in place”.

The Prime Minister provides no data as to how many such judges still work, 30 years after the fall of communism and almost 15 years after Poland's accession to the EU. He also fails to clarify what sort of influence those people might collectively have over ‘the Polish judiciary, or even what constitutes a communist-era judge’. If the main criterion was the fact they earned their university degrees during the communist times, then Morawiecki should place many of his party colleagues, including Jarosław Kaczyński into the same category of communist-era people. In light of such statements made by the Polish PM it is at best ironic that one of the Law and Justice's MPs responsible for pushing the reforms through the parliament is Stanisław Piotrowicz, a former communist-era prosecutor.

When criticising Polish judiciary the current administration refers, however, not only to moral corruption but also tangible benefits passed on to dishonest judges. This is once again Polish PM describing the state of the country's judiciary:

‘Favors go to friends. Vengeance is wreaked on rivals. Bribes are demanded in some of the most lucrative-looking cases. Proceedings have sometimes been dragged out interminably in the service of wealthy and influential defendants. Justice has too often not been available to those lacking political connections and large bank accounts.’

Again, Morawiecki fails to produce a single evidence that what he describes is a structural, omnipresent challenge and instead focuses on two [!] individual cases of judges' misconduct in order to accuse the whole group consisting of over 10 000 people. The exact same strategy has been applied repeatedly by the party and its acolytes. As was made clear by the European Council decision to trigger Article 7, all these claims failed to convince European officials. But did they convince the Poles?

Do Poles even care?

At first glance it may seem that the ongoing international feud over the judiciary has had no effect on the ruling party's political standing. As for now PiS absolutely dominates the political scene with popular support at around 40 percent. With opposition parties lagging far behind, PiS could even increase its parliamentary majority should Kaczyński decide to call snap elections any time soon. Why do so many Poles still support him?

There are, broadly speaking, two kinds of answers to this million-dollar question. The first is based on a notion that Polish society has significantly changed over the past few years. Whether this change was procured by external factors – like mass migration to the EU, or the crisis of the Union itself – or whether it's an expression of some deeply embedded characteristics of Poles as such, is yet another matter, which in this case can and should be put aside. That is because far more convincing is the second type of answer. It explains Law and Justice’s strength primarily by weaknesses of its opponents. The opposition parties failed to capitalize on the social unrest which has shaken Polish society deeply over the last two years, producing massive protests against the government.

The leaders of the main opposition party – Civic Platform – have been unable to present a credible alternative to PiS's actions in any important domain – from welfare policy, through social issues and the relations with the EU, to judiciary reform. Limiting its role to simply opposing the steps taken by the government, the opposition allowed the governing party to impose its narrative on every important subject.

Yet, popular support for PiS, though impressive, is far from solid. Only a few months ago, after the government waged an amateurish campaign to undermine Kaczyński's arch-rival Donald Tusk from being re-elected as the President of the European Council, popular support for the ruling party tumbled to around 25 percent. As the government continues to open up new international political conflicts some Poles may easily switch their support from PiS to a more pro-European and less militant party. What they need is an appealing story of how their country might be better-off without PiS in power, told by a credible opposition leader. As for now, both such a story and such a leader, are still to come.